Missing Architecture

Writing about what you know is easy; writing about what you don't is much harder. If there was something that might have been, but never was, how do you go about describing it?

That's the realm of this month's Venice etc... Specifically early Venetian architecture, and the unique partnership that produced our intriguing style of architecture and city planning. Yet it's not the architecture that still is nor once was, but the proposed buildings and structures, but never actually built, that truly expanded the Doge's vision of a new American renaissance. That's what I want to deal with here.

Venice, as we know, was the brainchild of Abbot Kinney, who came to California in 1880. His dream was to create an exotic city resembling the architecture and waterways of the famous northern Italian city. It would not be an ordinary beach community, but one devoted to high culture, truly unique architecture, and incorporating a "great university or institute."

For the initial layout and design of his exotic city by the sea, Kinney traveled to New York, hoping to convince Frederick Olmstead, the architect of Central Park, to join the team. Busy with projects, Olmstead recommended his young assistant, Norman Foote Marsh. Marsh initially agreed, joining forces with another young architect, Clarence H. Russell.

Marsh and Russell, young, striving architects, became associated around 1903 in Los Angeles in a partnership. Marsh took responsibility as the dominant partner. Successfully, Marsh & Russell designed Carnegie Libraries in Santa Monica, which opened in September 1903, Hollywood, and South Pasadena. Their partnership was off and running.

In 1904, Kinney contracted Marsh and Russell, based on their prominent background, to lay out a site plan and to design the first of the Venice community buildings. Influenced by Kinney's love of Venice, Italy and the World's Fair of 1904 in St. Louis, the firm of Marsh and Russell designed the look and flavor of Venice. On August 15, 1904 the first canal dredging began for the Grand Canal. The city of Venice was officially opened on June 30, 1905. Unfortunately, in 1907 the partnership between Marsh and Russell was dissolved. Marsh continued to work in Los Angeles and Russell went to San Francisco.

Norman Marsh was the seventh son of a family of nine. He was born in Alton, Ill. on July 16, 1871. He received his B.S. in architecture from the University of Illinois. His first job was as an engineer for the American Luxfer Prism company and he represented the company in Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York. For a brief time he worked as an architect in Chicago but moved to Los Angeles in 1900, drawn by the opportunities he believed he would find there. He moved to South Pasadena in 1902. He first formed a partnership with J.N. Preston which was of short duration and then later became associated with Clarence Russell. He was known, in the architectural community, as a specialist in college, school and church buildings.

We can be almost certain, even though no such specific record exists, that Marsh was influenced by the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago held when he was 22 years old. He must have gone to the Expo and seen the many and varied exhibits from all over the world, the lagoons, canals and bridges, and been influenced by the overall effect of the "planned city."

It's also intriguing how much of Venice resembled the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904, another architectural influence. The Grand Promenades, central lagoon, canals with ornate bridges, and glorious ceremonial buildings of the Beaux-Arts architectural style became the pattern Marsh followed. Venice was almost a conceptual carbon copy of this fair. Marsh undoubtably took the ideas and impressions from both Chicago and St. Louis with him to Los Angeles, which was ripe and ready for the ideal of the planned community and "City Beautiful" ideas, so prominent at the time.

It is recorded in the Architectural Record that Kinney gave Marsh and Russell practically carte blanche in designing the city and that $5,000,000 was projected as the initial cost of the principal structures and the canals. Marsh and Russell designed the buildings in keeping with the Venice and Renaissance ideas. The material and exterior finish of the buildings "have all been considered to evoke the feeling of Venice, Italy." No structure was allowed to exceed a certain height in keeping with the ideals of the "city beautiful." While the building of Venice was underway, Kinney was persuading shop owners to build their store fronts in an architectural style in harmony with the "Venetian Renaissance," in order to create a unified city, architecturally pleasing to the eye. The Saturday Post, owned and published by Kinney, promoted the city beautiful ideas which noted that a pleasure park was to be erected in the city of Venice for its residents, but that anything which "cheapens the residential section will be avoided." The beach resorts of Southern California "had 'growed' like topsy" and so they are considered crude. "This is where Venice has the advantage because," wrote the Post, "Venice has been planned so that it will appeal to the 'popular taste.'"

Marsh and Russell, in a full-agenda charette, designed the following buildings in Venice: the north side of Windward Avenue along with its arcaded street. These buildings were of brick and steel with concrete foundations. Also, the Hotel Windward, along Trolley Way, the Cabrillo (Ship Cafe), modeled after Juan Cabrillo's galleon, the Auditorium on the pier, with its seating capacity of 4,000, and the Palm Garden located in the Auditorium, which was built in only 28 days. The Ampitheatre at the lagoon, the entrance to the Midway, the Venice Bank building on the corner of Pacific and Windward, an apartment building at 235 San Juan Ave., and the University of the Arts, to fulfill Kinney's lavish dream, at 1304 Riviera Ave. Marsh and Graham, an unprincipaled member of the firm, designed the Hotel St. Marks, at Windward and Ocean Front Walk.

In January 1906, the architect Norman F. Marsh wrote of California's new improved version of Venice: "Like the Aladdin's lamp of nursery days, wealth and labor have been the wand that has transformed an uninviting landscape in the southern part of California into scenes that delight the aesthetic." In a period of twelve months, the architectural firm of Marsh and Russell had (according to Marsh's words) designed "a magic city (built for the generations) with its stately arcades, shimmering lagoons, floating pennants, and glistening minarets."

Later that same summer Marsh exclaimed, "Enjoying life for a few weeks by the sea and among the canals." A little bit of time away from his South Pasadena home was a grand diversion, to revel in the magnificent splendor of his architectural wonderment.

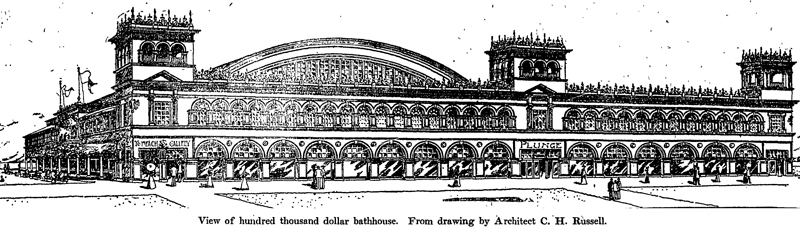

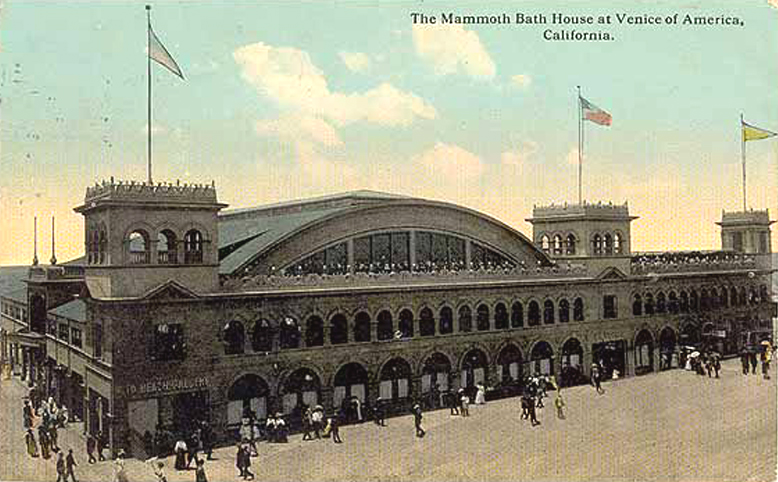

Although it is recorded that Russell moved to San Francisco after their split, he evidently returned to Los Angeles because subsequently both he and Marsh independently submitted designs for further buildings in Venice. In March of 1908, C.H. Russell produced plans and renderings for the ocean-side hundred thousand dollar Bath House, a handsome addition to the pretty city by the surf. Utilizing the Spanish Renaissance style, the structure featured large plate-glass windows on the western side, a 112 foot diameter glass dome over the 100 x 150 foot swimming pool, and electrical devices for creating startling effects in the water of the plunge. No foolin! Observation towers provided character to the building's appearance, and also afforded a great vantage point for looking seaward. This structure was one of the gathering points in early Venice, until urban-renewal attempts caused its destruction in the late 1940s.

The C.H. Russell Co., he being back in Los Angeles, also drew plans for the Union Congregational Church which was built and stood at the corner of Innes Place and Zephyr Ave. It was built of brick and mimicked the Lombardic Italian style of architecture. The firm also prepared plans for a large residence at the corner of Ocean Front and Breeze Ave. for Abbot Kinney. It was to be a two story building with a basement, tile walls, plastered exterior, and a clay tile roof, estimated at $25,000. He also presented plans for a one story brick building 50x100 ft. on Breeze Ave. near Ocean Front, also for Kinney. It was to contain store rooms or a moving picture theatre. He is also credited with the working drawings for the Exhibition Building to be erected on Windward Ave. Nope, none of these buildings never saw fruition. Just some of the lost structures of Venice.

Meanwhile, Marsh designed the Parkhurst Building, a two-story ornate brick Spanish revival building, at 2942 Main Street, built in 1927 by C. Gordon Parkhurst, a prominent realtor and next-to-last mayor of Venice. He also designed the Ocean Park Hotel, a "seaside hostelry," erected between Navy and Marine St. on Ocean Front Walk.

During those times, Eddie Maier had always been an early Venice booster. He and his brother owned a Los Angeles brewery and it was Eddie who brought the professional baseball team, the Tigers, to Venice. He hung out with the sports crowd, Hollywood bigshots, and that ilk. He also wanted a piece of the pier action. He saw all those people flock to Kinney's pier, thinking there must be room for one more.

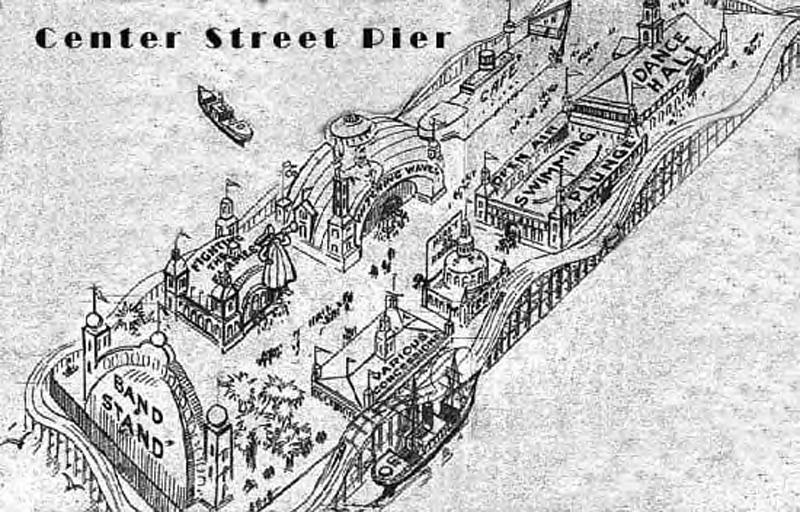

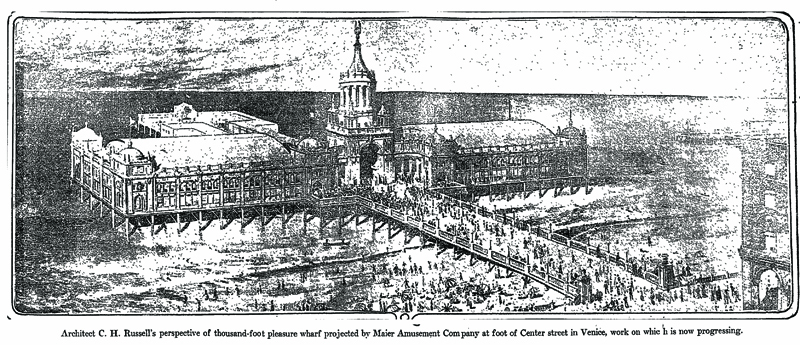

And so at the end of Center Street, today's North Venice Blvd., he proceeded to build his pier. As always, there's no specific date of when he did this, although there are photos of his pier as early as 1913. And the accompanying drawing shows a proposal from 1913. So I'd say, 1913.

A true carnival atmosphere is attended with this rendering. Along a wide promenade down the middle of the pier over the crashing waves below, one passes a café that looks coincidentally like a ship, then the Witching Waves attraction in a sultanic looking structure. Next comes the Fighting The Flames attraction, featuring a giant fireman to beckon the tourists in. At the end of the pier is an open area in front of the Band Stand. Music notes and all. Heading back toward shore we pass various concessions under a circus tent-like awning, then the Merry Go Round, and then the open air swimming plunge. Finally there was the Churchill Downs-appearing Dance Hall, at the mouth of the pier. And encircling the whole pier is a side-by-side racing roller coaster. Very inventive. Or possibly copycat. Anyway, we think that was what was intended to be built. We don't know if it was what was finally erected, but something was there.

The following winter was hellacious and brought a huge storm that battered his pier. On January 1, 1914, enormous waves, causing breakers twelve feet high, washed over the Venice Pier, doing horrific damage to that pier as well, along with enormous destruction to the entire ocean front. Waves dashed over Speedway, cutting their way 150 feet inland to that street. The damage was estimated at $100,000.

Seasiders who owned ocean-front property south of Center street, where the high tides wrought such destruction to the shore, found the concrete sidewalk and bulkhead washed away for a distance of fifteen blocks. This was directly where Maier's pier was located. And his pier fared no better.

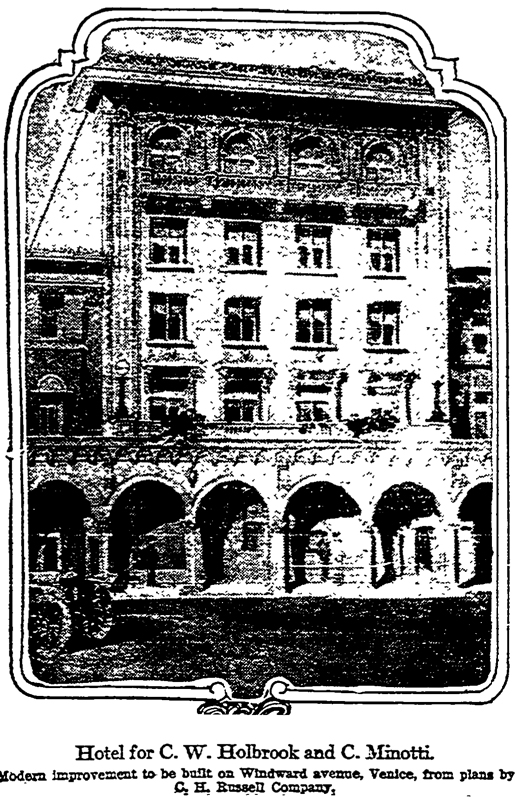

That May, Russell proposed a five-story and basement brick hotel for C.W. Holbrook and C. Minotti on Windward Ave. It would occupy a site 50x102 feet, designed in keeping with the other improvements along Windward, copying faithfully the architecture of the beautiful Italian city for which this beach is named. The hotel would contain 75 sleeping rooms, with about 20 baths. There would be a large reception room, a lobby and a grillroom on the ground floor. Sadly, this became another of those phantom architectural projects, one that was never built.

As reported in November of 1914, for two months or more workmen had been engaged in repairing the damage wrought by the unusually high waves last winter upon that portion of Maier's big pleasure wharf erected a year ago. In reconstructing such portions of the structure that were destroyed by storms, the progress already made was said to insure the early completion of the first unit of the pier.

C.H. Russell's grand proposal that month for a thousand-foot pleasure wharf to replace the old pier was presented to the Maier Amusement Company, along with the main buildings that rise above it. 300 feet from shore, the pier features two laterals, one to the north, another to the south of the grand main structure. The whole arrangement reminds one of San Francisco's Conservatory of Flowers, a glass-and-wood Victorian greenhouse. One side contains a mammoth dancing pavilion, the other a huge café. Totaling 1000 feet from ocean front to the seaward tip, one finds a band stand, with the pier widening outward like a fan at the end to give space for the assemblage of crowds. The shape of this band stand will be such that it will act as a sounding-board to make the music plainly audible from all parts of the pier. Sadly, this too was never built. A little too extreme for the times, I suppose.

Instead, to capture the spirit of the 20s, Maier built his Sunset Ballroom. The cock-eyed barn-like building sat squat on the pier, with a short extension hooking off to the north. Fortunately, it was then that a whole slew of musicians came to Venice, to help share the current rages of Chicago-based jazz, the Charleston dance trend, and the popular flapper dress style with the pleasure seeking masses. So, musicians Harry Baisden, Ben Pollack, Gil Rodin, Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller all converged on the Sunset Pier. Razz ma tazz!

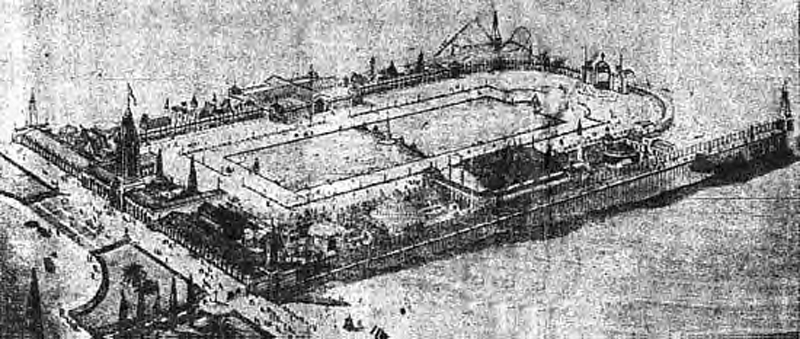

I guess a bit of the bubbly went to Maier's head, because in 1924, there was a rendering done of what was termed an "electric pier." And this was a whopper! A massive-looking proposal, looking to be about two blocks wide and extending hundreds of feet into the ocean, it featured a huge bathing pool in the center of the pier, with rides, dance pavilions, a grand entry tower, restaurants and carnival attractions all hugging the edges of the pier. It would have been a doozy, although again, this one never made it past the elegant sketch stage.

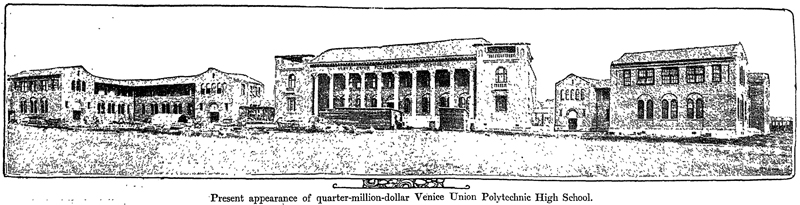

In the Los Angeles Times of November 8,1914, there was a dramatic layout featuring the new Venice High School. Under the headline "Splendid Educational Group Now Nearing Completion in Crescent Bay District. Present appearance of quarter-million-dollar Venice Union Polytechnic High School," it stated "The C.H. Russell Company of this city drew the plans for this great modern institution. The campus will house the scholastic activities of a progressive community that is making rapid strides in population and material development, and will take the place of a merely temporary building remodeled from the old Venice bath-house and long since overcrowded. The newest of the Southland's "Poly Highs" comprises five brick structures - an administration building, a science and household economy building, a manual arts building, a commercial building and a gymnasium, the whole being in the Lombardic style of architecture. The building enclose three sides of a quadrangle and are set well back of the "Short Line" right-of-way, in the midst of a thirty acre site." Unfortunately, the campus was all but destroyed on March 10, 1933 due to devastation caused by the Long Beach earthquake. The high school, which had become recognized as one of the most beautiful campuses in the country, was replaced with the still magnificent buildings that we see today.

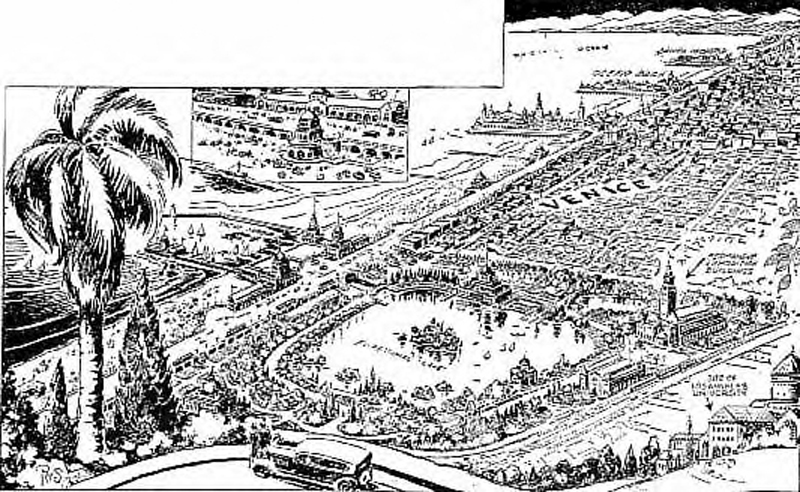

Now back to another non-realized project. Being the boom times of the Roaring-20s, there appeared another massive plan for a completely redone harbor and beach project. Appearing from the perspective from high above the Del Rey cliffs, this 1927 masterplan shows the entire coastline from Playa del Rey up to Malibu. Venice has maxed out with urban consolidation, and what is now the marina has been envisioned as an inland harbor, connecting to the ocean via a grand canal. The whole concept is reminiscent of the early layout of Playa del Rey, which featured an onshore lagoon and a hotel and pier, connected to both the lagoon and the ocean. This new configuration also contains a protected seaside harbor, grand ceremonial buildings along the shore, and a robust commercial district to the eastern side. Also included is the site of Los Angeles University, on the bluffs where Loyola Marymount is today. Quite a far-thinking plan, probably developed by some real estate visionary hoping to make a mound of cash. No city beautiful here. This, too, was just a pipe dream.

Unfortunately, and ultimately, Norman Foote Marsh, whose home was at 1934 Milan Ave., South Pasadena, died Sunday Sept. 4, 1955 at the age of 84 after a brief illness. His obituary stated that one of Mr. Marsh's early day architectural feats was planning the elaborate development of Venice, with its canal system, pier and famous Ship Cafe. He later headed the architectural firm of Marsh, Smith & Powell, architects for a number of large projects in the West. His presence in Venice will be forever remembered.

And so, in keeping with this history of unseen architecture, today's Venice recently arose to the occasion by blocking another piece of contemporary architecture. What was supposed to be the Hotel Ray, located on the 901 Abbot Kinney Boulevard property made famous as the office of Charles and Ray Eames industrial and graphic design, was defeated as being out of proportions with the community, by the local residents.

The 5-story sustainable "green" spa hotel was to include landscaped open areas, solar panels, heat exchange systems and usage of recycled materials. Stylish to the max, it also would feature 1165 square feet of ground floor retail space, a restaurant, and a 2750 square foot health spa.

Residents in opposition stopped the project by expressing concerns about traffic and parking issues, along with late-night sound abuse from the proposed roof-top lounge. But the major strength behind the opponents was the direct challenge to sections of the Venice Community Specific Plan by the developers. Instead of a maximum roof height of 30 feet, as stated by the Specific Plan, the developers were wanting a 55 foot roof height. They also proposed a floor area ratio of 2.06-to-1, while the allowable ratio is 1.5-to-1.

Ultimately, it was the Department of City Planning that nixed the project, much to the relief of the community. Another piece of architecture, gone to the dustbins. And, yet, Venice continues on, being the new architectural leader and focus of all of Los Angeles. Quite the impressive history, I'd say.

|